The Good Old Days

If watching the news, with its usual parade of terrible new developments, may have you throwing up your hands and exclaiming, “O tempora, o mores!” Yet I just came across an absolutely brilliant bit of analysis in the Washington Post that warns against the dangers of false nostalgia.

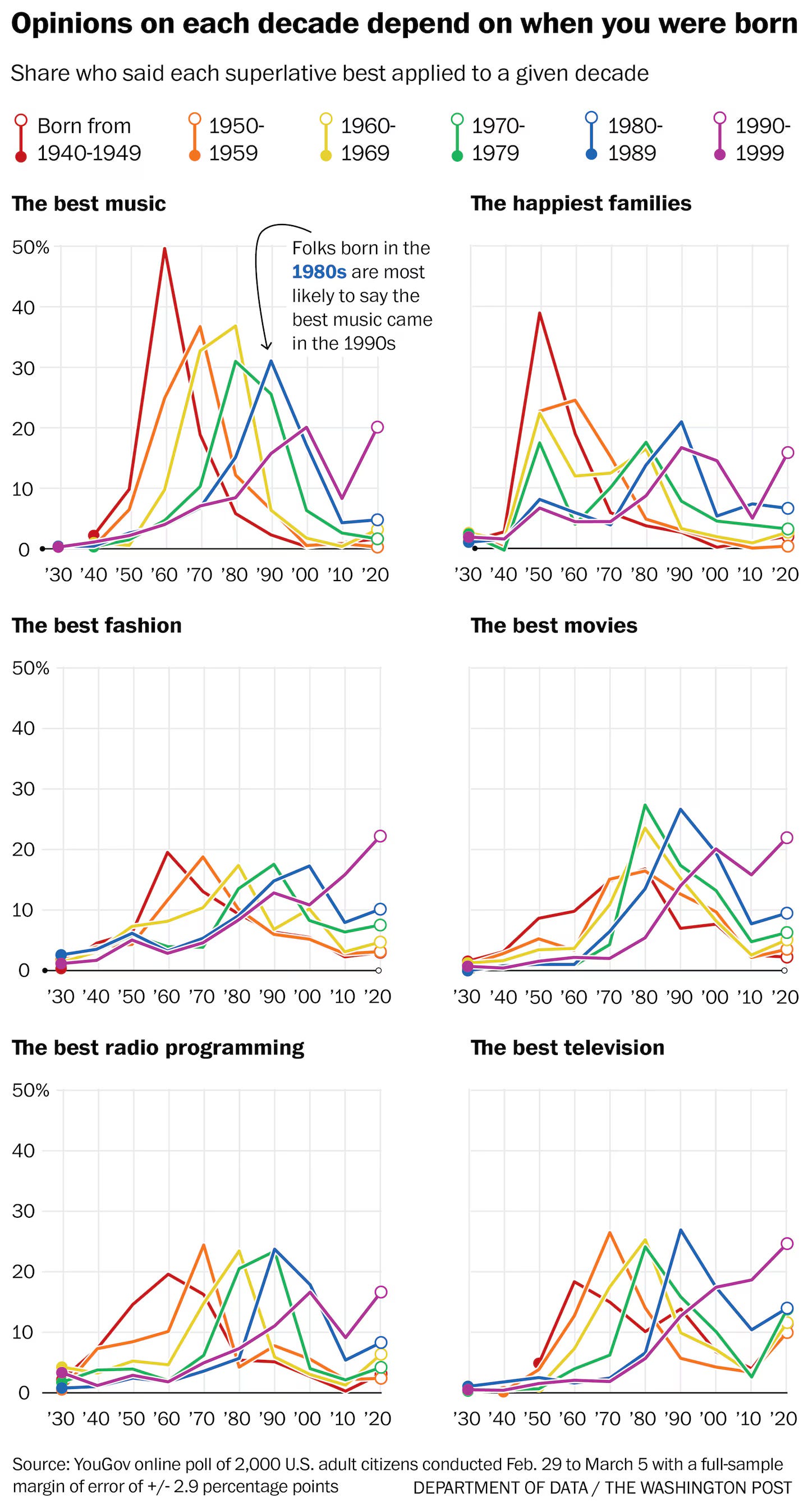

Pollsters from YouGov set out to find which era was “the good old days,” so they “asked 2,000 adults which decade had the best and worst music, movies, economy and so forth, across 20 measures.” They found no consensus.

We did spot some peaks: When asked which decade had the most moral society, the happiest families, or the closest-knit communities, white people and Republicans were about twice as likely as black people and Democrats to point to the 1950s. The difference probably depends on whether you remember that particular decade for “Leave it to Beaver,” drive-in theaters, and 12 Angry Men—or the Red Scare, the murder of Emmett Till, and massive resistance to school integration.

As one expert puts it, “nostalgia is colored by political preferences. Surprise, surprise.”

But any political, racial or gender divides were dwarfed by what happened when we charted the data by generation. Age, more than anything, determines when you think America peaked.

So, we looked at the data another way, measuring the gap between each person’s birth year and their ideal decade. The consistency of the resulting pattern delighted us: It shows that Americans feel nostalgia not for a specific era, but for a specific age.

The good old days when America was “great” aren’t the 1950s. They’re whatever decade you were 11, your parents knew the correct answer to any question, and you’d never heard of war crimes tribunals, microplastics, or improvised explosive devices. Or when you were 15 and athletes and musicians still played hard and hadn’t sold out.

This is not a big surprise. This article mentions another study a few years ago indicating that nostalgia for music tends to center around whatever was popular when you were 17. After that, you gradually become convinced that our music was so much better than that noise the kids are listening to these days.

It’s revealing how much nostalgia about economics and politics, not to mention the tempora and the mores, is formed at a very young age, often under the age of 10. This implies that everything looked better when we were surrounded by protective adults who shielded us from everything bad in the world—and when we weren’t responsible for anything.

The flipside of this is that for everyone, things are the worst in the present.

[A]lmost without exception, if you ask an American when times were worst, the most common response will be “right now!”

This holds true even when “now” is clearly not the right answer. For example, when we ask which decade had the worst economy, the most common answer is today. The Great Depression—when, for much of a decade, unemployment exceeded what we saw in the worst month of pandemic shutdowns—comes in a grudging second.

What follows is a discussion of “declinism” and the tendency of the past to always look better in retrospect than it felt at the time. We remember the good parts and tend to forget the bad parts. Their conclusion? Wait long enough and “the 2020s will be the good old days.”

The Good Old Days

I am fascinated by the idea that when we feel nostalgia, we are not feeling nostalgia for the way things were back then. We are feeling nostalgia for the way we were back then.

Similarly, I suspect that when we feel dissatisfaction with our current time, we are actually expressing dissatisfaction with our current stage of life (which we will later look back on with hazy nostalgia). So the Boomer conservatives who think the culture has gone down the tubes are to some extent just expressing the frustration of old age and the sense that they are no longer the ones shaping events in a world that is passing them by. Similarly, young conservative men who flirt with the alt-right and complain that feminism has ruined everything are often just complaining that they can’t get a date. It has become a cliché for them to report on moderating their views after they begin to get their lives together.

Among young people on the left, the version of this you hear most often is that the older generations have ruined the world for young people, who are unable to afford anything or live a decent life because everything is outside their reach. What they are actually complaining about is that they are in their 20s, an age at which they are no longer supported by the higher level of wealth accumulated by their parents, and they are still in relatively low-paying entry level jobs. They have entered an adult world where they see all sorts of enticing things they would like to own or enjoy, but they can’t afford very much of it yet.

This is not an economic condition caused by capitalism or even by any particular outside event or economic upheaval. It is merely one of the conditions of youth.

And this is why we need to rely on data rather than vibes to understand what is going on in the world. It turns out that even as every generation complains that the world was ruined by the generations before it, every generation is actually better off and wealthier at each stage of life than their forerunners. And that includes the latest generation to whine about their fate, Generation Z, according to an article in The Economist with the delightful title, “Gen Z Is Unprecedentedly Rich.”

In America hourly pay growth among 16- to 24-year-olds recently hit 13% year on year, compared with 6% for workers aged 25 to 54. This was the highest ‘young person premium’ since reliable data began (see chart 3). In Britain, where youth pay is measured differently, the average hourly pay of people aged 18-21 rose by an astonishing 15% last year, outstripping pay rises among other age groups by an unusually wide margin. In New Zealand the average hourly pay of people aged 20-24 increased by 10%, compared with an average of 6%.

Strong wage growth boosts family incomes. A new paper by Kevin Corinth of the American Enterprise Institute, a think-tank, and Jeff Larrimore of the Federal Reserve assesses Americans’ household income by generation, after accounting for taxes, government transfers and inflation. Millennials were somewhat better off than Gen X—those born between 1965 and 1980—when they were the same age. Zoomers, however, are much better off than millennials were at the same age. The typical 25-year-old Gen Z-er has an annual household income of over $40,000, more than 50% above baby-boomers at the same age.

None of this is a surprise, because that is exactly what we should expect in a functioning, dynamic economy—constant growth that ensures every generation will be better off than the one before.

As I pointed out a while back, we are becoming an upper-middle-class country. But we will get there while constantly complaining.

For related ideas, see my comments about sense of life, the blue dots of outrage, and the message of Groundhog Day. I have a feeling I am going to have to integrate all of these observations into a wider theory at some point.